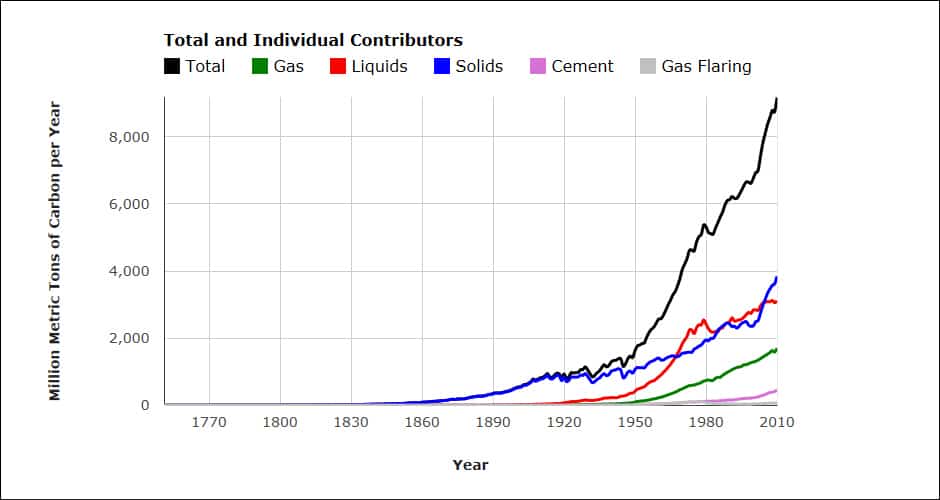

The United Nations has warned that our window of opportunity to tackle climate change and keep the global temperature rise below 2°C by 2100 is swiftly diminishing. In The Emission Gap Report 2013, compiled by 44 scientific groups in 17 countries, it warned that significant emission reductions are required by 2020 but as global emissions continue to rise, the gap between where we need to be and where we are is growing rapidly. The consequence is not only a rapidly reducing chance of keeping warming within the 2°C target, but also much more drastic economic and technological changes required to cut emissions fast enough.

View this in the context of the latest scientific report in the journal Nature which states that in order to have a 50% chance of meeting the 2°C target (which is not good odds!), we will need to leave two thirds of current fossil fuel reserves in the ground. As Naomi Klein explains in her book This Changes Everything, these reserves are not total fossil fuel under the earth’s surface but fossil fuel reserves that are already earmarked for exploitation. In other words, reserves that fossil fuel companies are already planning to exploit, have already invested in and that contribute a huge amount to the share price of these companies. If governments legislated to prevent these reserves being dug out of the ground, the share price of these corporations would collapse.

However, as George Monbiot pointed out in his recent article for The Guardian, no government has ever publicly considered the idea of limiting fossil fuel production and many including the UK have policies to maximise it. We are seeing examples of this with calls for the government to help North Sea oil production and also in its support for hydraulic fracturing (aka fracking) for which the New Forest has been earmarked as a potential area for exploitation . The reality is that if resources are extracted, they will be burned, explaining why current global climate policies are inherently flawed and why emissions have risen steadily since the first climate treaty was signed at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992.

When viewed in context then, 2°C of warming by 2100 is an optimistic scenario unless we act fast to make the radical changes in political policies, industries, technologies and lifestyles that are required to deliver genuine emission cuts.

So how will the 2°C global rise in average temperatures affect the New Forest?

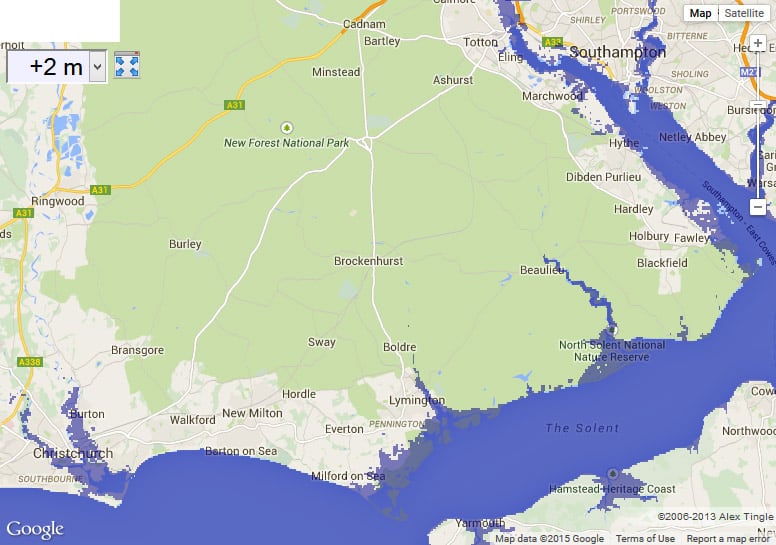

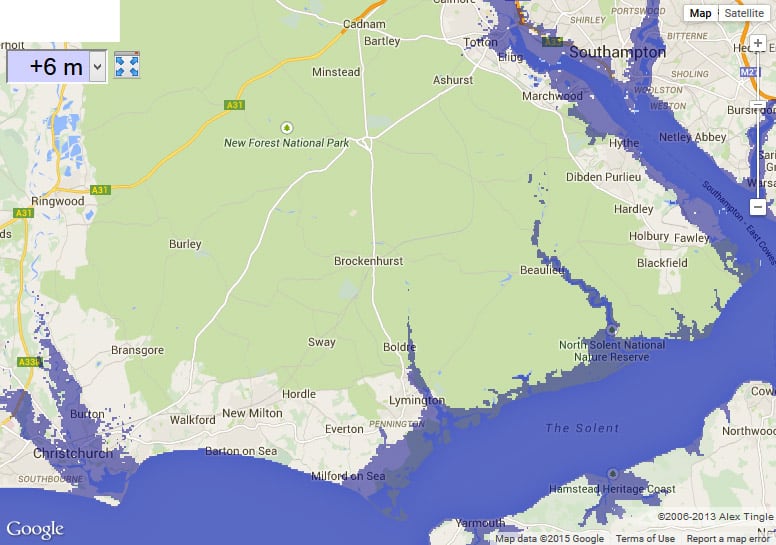

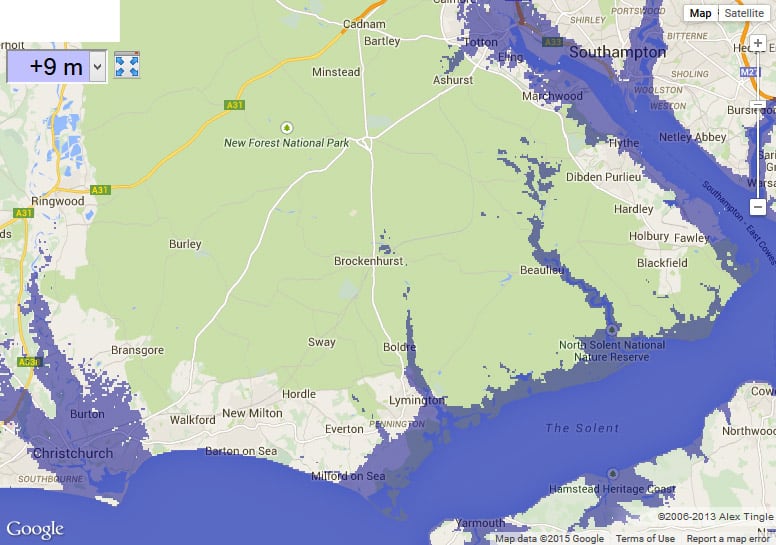

One of the biggest changes would be the increase in summer temperatures, which could see us regularly hitting 40°C during summer heatwaves. This will inevitably have a big impact on local wildlife that would struggle to adapt fast enough to the changing climate, and also to agriculture within the forest. As a coastal area, the New Forest will also feel the impacts of rising sea levels. The extent of this is currently unknown but estimates vary from the IPCC’s self-confessed optimistic estimate of 0.6 metres to the SARC estimate of 1.4 metres and more recently a paper in Nature led by Robert Kopp of Princeton University predicting 6.6 to 9 metres. Even a 1 metre rise in sea levels would cause significant flooding on the coastal and riverside edges of the forest including Lymington, Milford and crucially Fawley.

If you look at higher prediction levels of rising then flooding could devastate the coastal areas of the forest even as far up as Totton and also nearby towns such a Southampton and Poole.

This brings us on nicely to the economic impact of global warming. Even with a conservative estimate of a 2°C rise, the economy of the New Forest will be drastically affected. The biggest impact of all would be the somewhat ironic flooding of the Fawley oil refinery, which is the areas largest employer. In addition, flooding would have great economic and human cost, damaging areas such as Lymington, particularly the marina and Isle of Wight ferries that both bring significant income to the area. The loss of local wildlife and increasing summer forest fires will also likely have a negative impact on tourism and agriculture. A further blow to the local economy would come if the container and cruise ports in Southampton were disrupted by rising sea levels, highlighting yet again in the irony that our area of outstanding natural beauty is to a large extent dependent on high carbon industries.

Not only would a 2°C in rise devastate the natural environment of the New Forest, it also has the potential to devastate the local economy if we don’t have act fast enough.

Is there any good news?

It might all sound like doom and gloom, but it is essential that we face up to the scientific reality in order that we can respond accordingly.

The good news is that although the New Forest can not alone prevent runaway climate change, we can as a region, a community and as individuals make changes to minimise our impact and building a more resilient, future-proof economy while we still have the time and resources to do so, but that means we need to act now.

We firstly need to accept that the Fawley oil refinery cannot be part of a long term economic plan for the New Forest, both due to its contribution to climate change and due to the likely practical issues of rising sea levels. However, the New Forest is fortunate in having a huge opportunity to develop a clean energy economy that helps to fight climate change and fuel a robust local economy.

Our coastal location, sunny micro-climate and low population density put us in a strong position to not only be self sufficient in clean energy such as wind, solar and biomass but actually be a net energy exporter. This can be achieved with negligible impact on local landscapes but it requires buy-in from local communities and progressive thinking from planners.

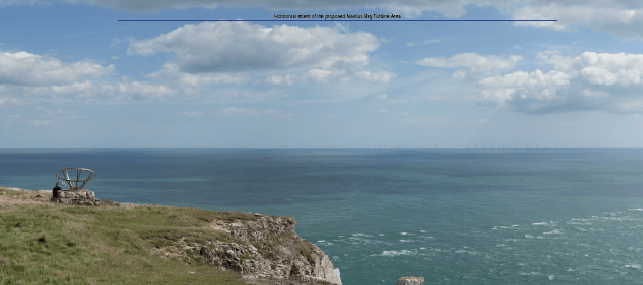

For example, the Navitus Bay offshore wind farm is a huge energy resource that has sadly already been scaled down due to fear of microscopic visual impact for those owning seafront homes and also a 5MW solar farm near Hordle was recently rejected by planners on the basis that it constitutes “industrialisation” of the New Forest. This was a somewhat bizarre decision for an installation that would be almost invisible, was supported by local communities, would provide a large amount of clean energy and would still allow space for grazing animals, which was the previous land use. Not to mention the fact that the chimneys and flaring from Fawley oil refinery can be seen for miles across the forest, which makes any claims if industrialisation highly hypocritical. However, what both of these schemes lacked was local ownership and this is where the big opportunity lies. Buy-in for renewable installations (even onshore wind) is generally very positive when the local people have a significant financial state in the project. Community owned renewables as demonstrated by projects like the West Solent Solar Coop in Pennington allow local people to reap the financial rewards of clean energy while also having the potential to reduce fuel bills for families, pensioners, schools, businesses and hospitals if planned well, further boosting local economies and improving public services.

In addition to larger renewable installations we should be heavily incentivising installation of domestic solar and energy efficiency improvements, making the New Forest leading centre of sustainable building. All it needs is vision and leadership from local planners to demand the highest standards, which will then also benefit home owners and tenants in the long term through reduced energy bills, helping to take fuel poverty. Planners also need to think more carefully about rising sea levels and river flooding when considering new developments in coastal areas in order to avoid future problems.

This will also require support for local businesses to train staff in new energy technologies and efficiency measures, creating a skills hub that allows local businesses to offer high value future-proof services to communities not just locally but also nationally. It is important to note that although the New Forest currently has a high economic dependency on fossil fuels, renewable technologies and energy efficiency technologies employ many times more people per pound of economic activity than fossil fuels, with far more of the money staying within local economies instead of floating away to foreign oil producers and multinational corporations.

We should also consider a similar opportunity to improve the local economy, quality of life and environment through changes in local agriculture. As a rural area, increased local food production can employ more people, keep more money within the local economy and help to protect local people from increases in global food prices. This will be a challenge considering the climatic changes ahead but small scale organic agriculture (specifically arable) has been proven to have lower climate impact, improve soil fertility, increased yield per hectare, increased biodiversity and better resistance to natural threats such as droughts, floods and pests. Not to mention the potential for increased local food production through conversion of some land from pastoral to arable farming as suggested by the report Zero Carbon Britain but also conversion of paddock land to food production. If well managed, such changes could deliver huge benefits to local people and the environment without negatively affecting the open forest areas that are so important to our quality of life and tourism sector.

It’s time to embrace the challenge

There is no doubt that minimising climate change and adapting to its affects are both immense challenges for people throughout the world and the New Forest is no different.

2100 might sound like an abstract date far in the future, but consider that any child born this year will be 85 years old in 2100, that many of the impacts will kick in long before then as we are already seeing and that 2°C is looking like an increasingly optimistic prediction, then there is no doubt that radical, positive action to build a clean and robust local economy for the New Forest must begin now.